Nanopore Signal Data, The SLOW5 Format, and You

In this document we provide a brief overview and explanation of nanopore signal data in relation to the SLOW5 file format. We explain what nanopore sequencing is, how we observe and interpret the data, and how SLOW5 fits into all of it.

Table of Contents

- Nanopore Signal Data, The SLOW5 Format, and You

- Table of Contents

What the Heck is a Nanopore?

Nanopore sequencing is a method of capturing the nucleobase sequence of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) or RNA. This specific method involves driving single strand nucleic acids through a nanoscopic protein pore by an applied voltage. This protein pore is sensitive to the nucleobases being fed through it, and will change in conductivity depending on the nucleobase sequence inside the pore. By measuring the conductivity of the pore, we store this signal data, and later map it to the base sequence of our ssDNA and RNA.

The Setup

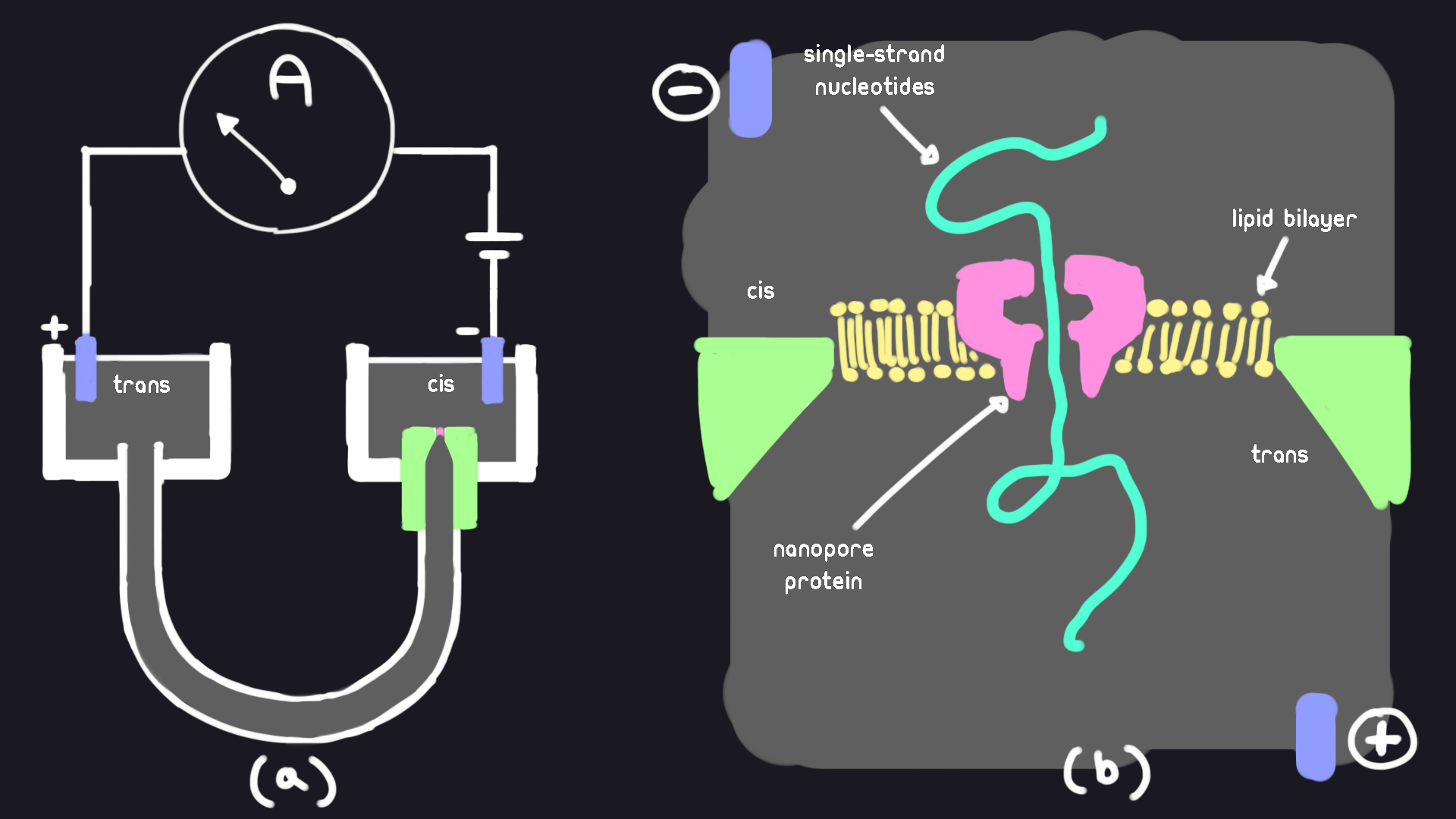

This figure shows a hypothetical nanopore setup. DNA strands are drawn through the nanopore by applying voltage. An ion-containing fluid is channeled through a nanopore in the lipid bilayer. The lipid bilayer separates two chambers filled with buffered potassium chloride solutions (KCl). The chambers are named cis and trans respectively.

(a) The chambers cis and trans are interconnected via a U-shaped tube. Both chambers are filled with KCl. A voltage bias is applied via the electrodes in each chamber. This bias pulls ions and molecules from the cis side to the trans side. An ammeter measures the ionic current flowing from the cis chamber to the trans chamber.

(b) Magnification of the cis chamber. The pore in the cis side provides the only connection between the two chambers. This is the only point where ions and molecules can move from the cis side to the trans side.

α-hemolysin was the original protein chosen during the early days of nanopore. The reason it was so suitable for the job is because it forms a ~1.5nm opening through the ion-impermeable lipid-bilayer. This diameter, whilst much larger than the ions of the KCl solution, allowing for easy passage; can only just fit a single polynucleotide of DNA (~1.2nm), and cannot fit double-stranded DNA (~2.4nm).

Ideally, to accurately map the current to the passage of nucleic acids through the nanopore, we must be able to control the rate at which the strand is being passed through. To solve this, a motor protein (that is unable to fit through the pore), is attached to the end of a ssDNA/RNA strand. Enzymes such as helicases and polymerases have the advantage of traversing though DNA in distinct steps, without needing any additional external source of energy applied. Now when a strand is pulled through the nanopore, it can only go through as fast as the motor protein allows it.

The Data

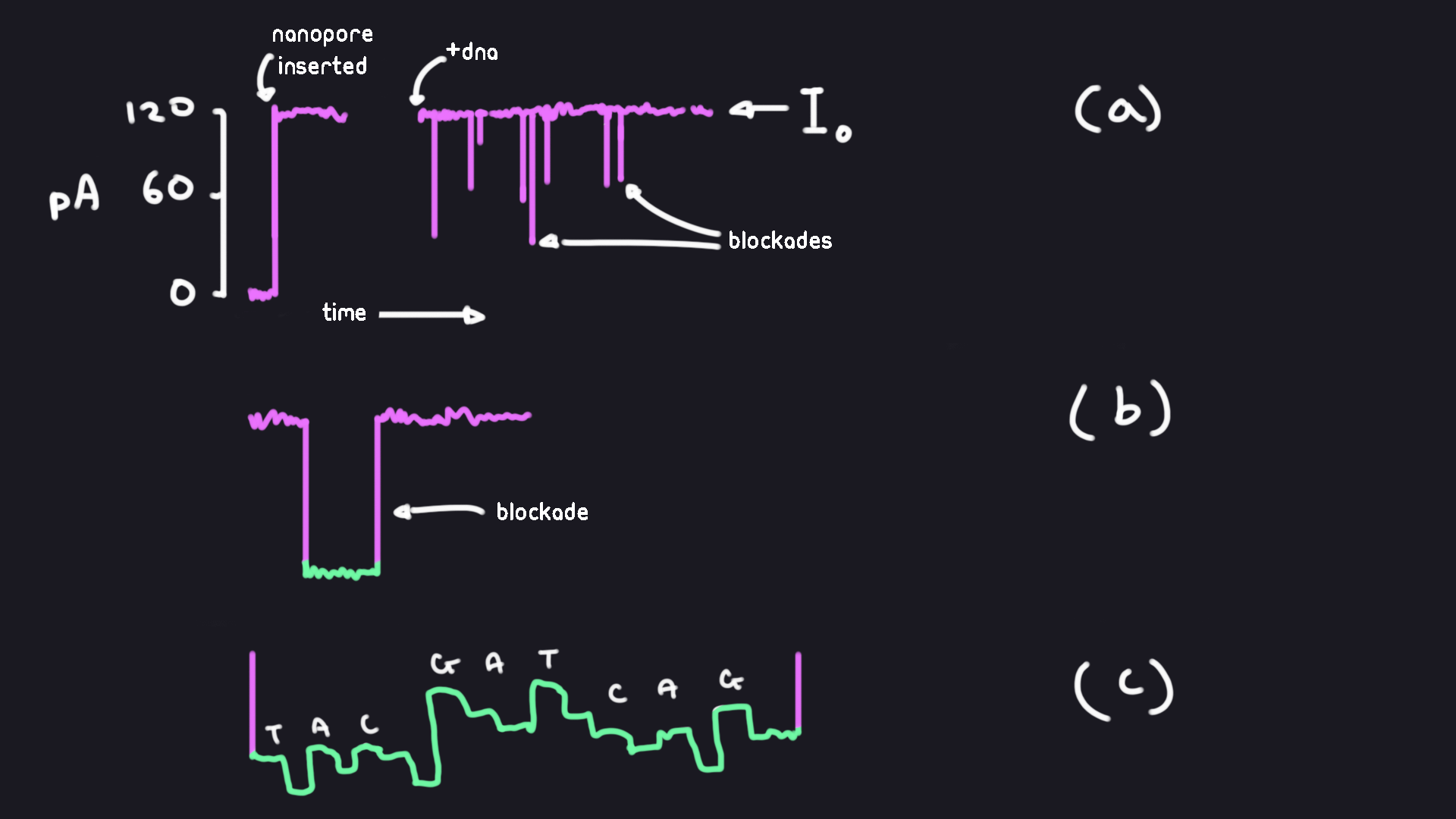

Tranditionally, a voltage bias of ~120-180mV is applied between the two sides of the KCl solution. Without the nanopore protein, no ionic current can be measured through the lipid bilayer. Once the protein inserts itself into the bilayer, ions will start flowing through and we see an increase in the measured ionic current. This baseline current it increases to is called the “open channel current”. When ssDNA or RNA is added to the cis chamber, we begin to see sudden drops in the measured current. We call these transient reductions “blockades”. Small modulations in current are sometimes found in these blockades.

(a) Example measured current over time. We see an increase in current once the nanopore is inserted and an ion flow created. The open pore current Io is our baseline current. Most blockades that occur are observed to be the result of polynucleoptide strands being pulled through the pore.

(b) View of a single blockade magnified.

(c) Small modulations in current we might see in a blockade. These modulations are interpreted as corresponding to specific DNA or RNA bases.

Current Limitations

The nanopore proteins used today have a sensing zone of a minimum 4-5 nucleobases. What this means is that we cannot create a 1-1 mapping of the signal to individual nucleobases. Until a nanopore protein is found that can produce a current reflecting a single nucleobase, we rely on computational algorithms and techniques to decode nanopore signal data.

Furthermore, as is typical with physical measurements, many different problems can and will almost always occur during sequencing. For example, nanopores can get saturated or blocked, the motor enzyme might step through the bases too quickly for an accurate measurement, signals expressed by different base sequences may be too similar for basecalling, the pysical nucleotide strands themselves become damaged, etc.

ONT’s MultiPore Setup (Flow Cells)

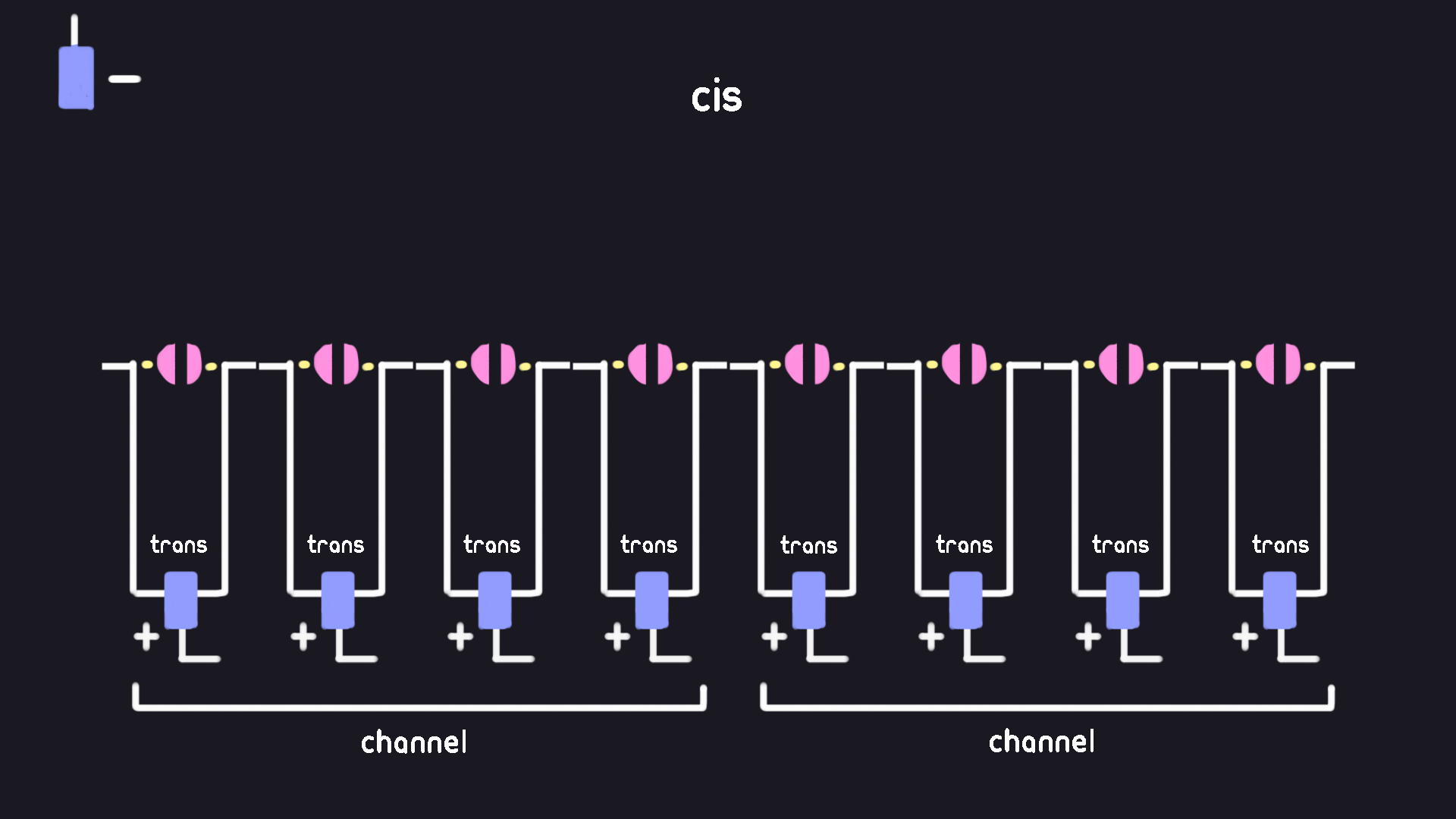

ONT nanopore setups follow pretty closely to the previously illustrated examples, but are more tailored towards high-volume sequencing. The setup of these sequencers are relevant to the slow5 file format as many fields will depend to external events and physical attributes of the nanopore device. Mux status, read numbers, and channel ids are all important markers for analyzing your sequencing runs. Researches may use these datapoints to evaluate the efficacy of enrichment techniques, or identifying problematic transcripts. Here we will specifically look at the MinION device, but all devices will output either the legacy FAST5 or new POD5 file format, and the setup discussed will generally be applicable to all ONT nanopore sequencers.

Sensor Array, Wells, and Channels

In order to start sequencing DNA, the MinION must take in a disposable component called a “flow cell”. You can think of a flow cell as a hot-swappable version of the cis and trans liquid chambers discussed in the setup before. Basically, because things get damaged during experiments we make part of the setup a replacable component. Once the flow cell is too damaged to function, we throw it out and get a new one. Coincidentally, this is also a good monetization model for ONT.

A MinION flow cell holds 2048 total sensor “wells”. Each well holds a single nanopore between a shared cis chamber and its own individual trans chamber well. Each trans chamber well contains a electrode at its base where the current can be measured. Despite containing 2048 sensor wells, the MinION can only measure 512 simultaneously. Thus, each of the wells are organised into groups of 4, which we can refer to as “channels”. The sequencer will select best performing well in each channel to have its current recorded.

Mux Scan, Mux Status, Mux Selection

As discussed before, current nanopore instruments are not impervious to physical damage and defects as part of the sequencing process. Over time, wells in the nanopore device can become temporarily or permanently blocked from producing a readable signal. To combat this, nanopore sequencers will periodically analyse the health of each well called the “mux scan” or “pore scan”, and select the healthiest well in each channel in a process called “mux selection”. The health of the pore is diagnosed during this stage, and its actual diagnosis is refered to as its “mux status”.

In addition to mux selection, if the device thinks a pore is blocked or clogged with something, the MinION may also attempt to eject any DNA or contaminants that might stuck in it. This is done by applying a voltage that briefly reverses the ionic flow through the pore in hopes of clearing it out.

Signal Conversion

The analogue signal measured undergoes digital conversion via the Analog to Digital Converter (ADC) before it can be stored in memory. We refer to the digital signal output by the ADC as our “raw signal”. To convert this raw signal back into an approximation of our actual analogue signal in pico amps, we use the following equation:

signal_in_pico_ampere = (raw_signal + offset) * (range / digitisation)

The raw_signal is the one stored in file, and must be converted into signal_in_pico_ampere when we want to use it. We will revisit these parameters when we look at the SLOW5 file format.

Why SLOW5?

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) is the leading commercial provider of nanopore sequencing. The default FAST5 file format was not optimal for the large amounts of data processing and manipulation required for interpreting nanopore signal data. Hence, SLOW5 was developed to overcome inherent limitations in the standard FAST5 signal data format that prevent efficient, scalable analysis and cause many headaches for developers. Since then, POD5 was developed by ONT and has now become the new default output format for their nanopore platforms. However, SLOW5 still offers equal or better performance than POD5 and with a simpler specification. More importantly, SLOW5 as a format is fully mature and will likely not see any breaking changes for the forseeable future. This makes tooling/development with SLOW5 simple, maintainable, and accessible not only for developers but also researches looking into an efficient and stable file format.

Whats Inside My SLOW5 File?

SLOW5 stores the metadata and raw signal output of DNA/RNA sequencing runs completed through ONT nanopore platforms such as the PromethION, and MinION. Metadata can be viewed in the header of each SLOW5. Distinct partitions of signal data captured by the sequencing run is stored in separate records or “reads” in the body of the SLOW5 file.

Here we will use slow5tools, and files from a small slow5 file for example usage.

The full specifications of each SLOW5 version can be found here: slow5 specs.

Header

The header of a SLOW5 file will contain all the meta data associated with reads in your file. It is located at the start of the file. The header is usually only looked at if you need information about the experiment itself, or the hardware it was performed on.

# view the header of a slow5 file

slow5tools skim --hdr reads.slow5

Here are some fields in our example file:

@device_type promethion # ONT platform the data was sequenced on

@hostname C48B226 # name of the device that hosted the run

@sequencing_kit sqk-lsk114 # kit used by the ONT nanopore sequencer

@distribution_version 22.12.5 # the version of MinKNOW used for the run

@sample_id A12878 # name of the sample given by the user

@experiment_duration_set 320 # how long the run went for (minutes)

@sample_frequency 4000 # no. of data points collected per second

There are many more fields, and most of them are for advanced users that require a more detailed explanation. The full specification can be found here: slow5 specs.

Records (Reads)

Each strand of ssDNA/RNA that gets sequenced through a nanopore has its resulting signal data stored into a SLOW5 record or “read”. Each read is identified by a “read id”.

# get all the read ids contained ina slow5 file

slow5tools skim -rid reads.slow5

# read ids contained in our example

00002194-fea5-433c-ba89-1eb6b60f0f28

00013808-f7cb-4c36-8cdd-265aba0a7487

0001960d-c143-4faf-bf20-753b9041812a

...

00049d1a-a957-472b-a1a1-86e4dac6c568

# view all the fields of each read in a slow5 file

slow5tools skim reads.slow5

SLOW5 Record Primary Fields

Here we go into detail of each primary field of a SLOW5 record. These fields are mandatory and thus will appear in every SLOW5 record you come across.

read_id | string

Simply the unique ID for each record in a particular SLOW5 file. Looks like ‘00002194-fea5-433c-ba89-1eb6b60f0f28’.

read_group | uint

The read group that this particular record belongs to. Read groups are identified by their order in the header, so a file that contains only a single run will have all records pointing to the read group 0. This is explained in more detail later.

raw_signal | [int_16]

This is the raw signal value output by the ADC on our nanopore device (for this read). We store our raw signal as list of 16-bit integers. The raw signal is not a direct representation of the analogue signal measured and must be converted via the following equation:

signal_in_pico_ampere = (raw_signal + offset) * (range / digitisation)

len_raw_signal | uint_64

The number of values (samples) in our raw signal. If we have 100 samples for this read, len_raw_signal = 100.

digitisation | double

Refers to the number of quantisation levels in the Analog to Digital Converter (ADC). For example, if the ADC is 12 bit, digitisation is 4096 (2^12). This is sometimes referred to as the “resolution” of our digital signal.

offset | double

This is just a value we need to add to our raw signal when it’s converted into pico amperes.

range | double

The full scale measurement range of our signal in pico amperes.

sampling_rate | double

Sampling frequency of the ADC. Just think of this as how many times the signal is sampled every second by the nanopore device.

SLOW5 Record Auxiliary Fields

Auxiliary fields may not be present in every SLOW5 file, these are just the common ones. Many of these fields are closely tied to the sequencing structure of an ONT nanopore device, and the whole mux scanning process. I highly recommend you familiarise yourself with the previous section detailing a typical ONT device setup before skipping to this bit.

channel_number | string

This simply indicates the channel that this read was sequenced in. It’s stored as a string, but so far has only been used to represent numbers.

median_before | double

The estimated median current level that was recorded immediately before the read begins. Usually, pore is in an open state before the read. You can think of this as the median current level right before a blockade.

read_number | int

When a channel’s signal is recorded as a read, the device keeps track of what order a read appears in. So for a record with channel_number=5 and a read_number=100, we know that the record was the 100th read sequenced in channel 5. It is also important to note that not all reads are recorded into the file.

start_mux | uint

This is the MUX setting for the channel before the read begins. Remember that Mux settings are calculated on a per-channel basis, with a channel containing multiple wells.

start_time | uint

The time that this read began. This is measured in the number of samples taken since the run had started.

start_time_in_secs = start_time / sampling_rate

Read Groups

Multiple different runs can be stored in a single SLOW5 file. Doing so will organize the data into different “read groups”. Metadata associated with each read group is stored in the header in their respective fields. Each read in a SLOW5 file contains the field read_group, indicating the read group it belongs to.

Small Example Uses

Here we will use slow5tools, and files from this directory for example usage.

# print the stats of a slow5 file

slow5tools stats reads.slow5

# convert fast5 files to slow5 files

mkdir blow5_dir && slow5tools f2s fast5_dir -d blow5_dir

# merge all the slow5 files in to a single file

slow5tools merge blow5_dir -o reads.blow5

# convert slow5 to blow5

slow5tools view reads.slow5 -o reads.blow5

# extract 5 random reads from a blow5

slow5tools skim --rid reads.blow5 | sort -R | head -5 > rand_5_rid.txt

slow5tools get reads.blow5 --list rand_5_rid.txt -o reads_subsubsample.blow5

# fetch a single read from a slow5 file

slow5tools get reads.blow5 00002194-fea5-433c-ba89-1eb6b60f0f28

More advanced uses can be found in the full documation: slow5tools docs.

The End

Congratulations! You made it! Have a gold star: ![]() . This tutorial was written by BonsonW. If you think this tutorial requires any changes, feel free to ping me in an Issue.

. This tutorial was written by BonsonW. If you think this tutorial requires any changes, feel free to ping me in an Issue.